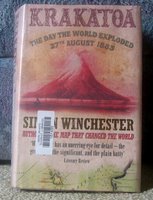

Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded 27th August 1883 by Simon Winchester

This book caught my eye at the Tokoroa Public Library. I’d heard of Krakatoa, but didn’t really know anything about it. I quickly learned that Krakatoa is considered the 5th largest volcanic eruption in recent geologic history. In decreasing order of size, the eruptions were:

1. Mt. Toba (Indonesia), 74,000 years ago (I’m not sure I consider this one recent compared to the other four).

2. Tambora (Indonesia), 1815.

3. Taupo (New Zealand), AD 180 (we are only 60 km from Taupo, but it is thankfully considered dormant)

4. Katmai (Alaska), 1912.

5. Krakatoa (Indonesia), 1883.

This book certainly did impress upon me the enormity of Krakatoa’s 1883 eruption. The island basically blew itself into oblivion, leaving just one peak behind. Airwaves reverberated around the earth 7 times and were detected in Europe and North America. The sea was filled with floating pumice, making it difficult for boats to navigate the waters. 36,000 people died, mostly from the tsunamis created by the eruption. This is the kind of stuff I was interested in. Winchester did a good job of including eyewitness testimony of the events. The unfathomable things that were witnessed continue to remind me that truth is often stranger than fiction (hence my fascination with non-fiction).

But with 391 pages of text (excluding references and index), Winchester doesn’t just talk about the facts of the eruption. He links Krakatoa to numerous social trends and technological advances. For example, he talks at length about the telegraph lines that allowed news of the explosion to be communicated around the world faster than was ever possible before. Towards the end, he also links Krakatoa’s devastation of Sumatra to the rise of radical Islam in Indonesia.

Although interesting, this book was incredibly long-winded. Winchester abuses the footnote, often writing whole paragraphs. I didn’t count, but I think he averages a footnote for every other page. As if the footnotes weren’t enough, he frequently goes off on tangents (sometimes interesting ones). For example, 200 pages into the book, right when he’s getting to the big eruption, he goes off a tangent about a circus that happened to be performing in a nearby city prior to the eruption.

The author almost lost me in the first two chapters of the book. He went on and on about Dutch colonial history in Indonesia. I actually skipped ahead to chapter 3, which is something I never do in books. Luckily, chapter 3, Close Encounters on the Wallace Line, was my personal favorite. Here he explained why Krakatoa is where it is. The subduction of the Australian Oceanic Plate under the Asian Plate has created numerous volcanoes, forming many of the Indonesian islands. Central to this explanation is the theory of plate tectonics. Chapter 3 is a short history of the development of this theory. Alfred Russell Wallace (of Wallace’s Line) has been largely forgotten in the history of the development of the theory of natural selection, but his writings had a significant influence on Darwin’s writing (from what I’ve read of each of them, Wallace was much easier to understand). Wallace spent years in southeast Asia studying the flora and fauna, and he noticed a division (the Wallace Line) between the plants and animals of Australian origin and Eurasian origin among closely spaced islands. Today, we know that this is a result of the meeting of the Australian Plate and the Asian Plate- just like Krakatoa. Another major character in chapter 3 is Alfred Wegener, advocate of continental drift. Although Wegener had fossil evidence that the continents were once joined, he couldn’t explain the mechanism by which they moved and was widely ridiculed. It wasn’t until 35 years after his death, in 1965, that plate tectonics was widely accepted. I am absolutely amazed that this earth-shaping mechanism has only been understood for the past 40 years. That’s well within the lifetime of many of you reading this now! Incredible.

I highly recommend chapter 3, but other than that I found the book to be lengthy, sometimes repetitive, and written in a tone that makes it seem much older than its publication of 2003. Winston talks about people in a somewhat non-PC way, which also makes this books sound like it was written shortly after the acceptance of plate tectonics. Right at the end, he really annoyed me while talking about the colonization (by plants and animals, not people) of the newly formed Anak Krakatoa. He wrote, “…And as the forests thickened, some amphibians that had somehow found their way across the sea began to slink in and make their nests- monitor lizards, paradise tree snakes….” Snakes and lizards ARE NOT amphibians; they are reptiles. This kind of mistake is just careless. The only possible excuse would be if this book were written 100 years ago when amphibian (both life in Greek), not just amphibious, could refer to animals (including mammals) that spent part of their lives on land and part in water. I think the book could have been much better (and shorter) with aggressive editing.

If you’re interested in reading more about Krakatoa, I recommend the Wikipedia article: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krakatoa

Carrie

P.S. If you're interested in reading more about Alfred Russell Wallace or Alfred Wegener, check out their wikipedia articles:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Russell_Wallace

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Wegener

2 comments:

PC ain't where it's at, baby.

PC ain't where it's at, baby.

Post a Comment