Lions of Tsavo: Exploring the Legacy of Africa’s Notorious Man-Eaters by Bruce Patterson

This is a very long post that has nothing to do with New Zealand, but it does have a lot to do with my time in Kenya. This book has intersected remarkably with my own life in many unanticipated ways. I’ll explain that later, though.

Bruce Patterson is a mammologist at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. This book covers a range of interesting physiological and ecological questions brought up by two famous lions killed in 1898. During the construction of the Kenyan railroad from the Indian Ocean to Lake Victoria, about 135 workers were killed by two male lions before they were shot. Their skins are now on display at the Field Museum. The movie Ghost in the Darkness is based on this story (I haven’t seen the movie so I can’t say how closely).

The first part of the book examines the story of the Tsavo man-eaters as well as other man-eating lions to identify potential causes of human hunting. It seems to be a combination of factors, including reduced availability of normal prey items, scavenging human bodies after epidemics, and injury to lions that prevent them from hunting the harder-to-kill prey (humans are quite easy). These chapters are incredibly gripping (and often gruesome).

Besides eating people, the Lions of Tsavo are remarkable because they are nearly maneless even though they are adult males. Maneless lions are still found in the Tsavo region (and elsewhere) today. The second part of the book examines potential explanations for the causes of manelessness in lions. In 2002, Patterson started studying lions in the Tsavo area by radio collaring a male, ‘Romeo,’ and following the behavior of prides and individuals. In short, it seems that Tsavo is so hot and dry that the physiological disadvantage of having a mane is greater than the sexual advantage of having one.

Patterson also addresses the complex relationships between humans and lions. We kill them to prevent them from killing us, sometimes we let people pay a lot of money to kill them, and we’re still trying to protect them without compromising the safety of people that have live with them. I find these kinds of dilemmas fascinating and resolving them is incredibly important for conservation all over the world.

Overall this book is captivating and easy to read. I especially like the way Patterson presents the testing of various hypotheses about lion ecology. The book seems to be well-edited, although I did find two footnote errors (one was on the wrong page and one was duplicated). Much of the research Patterson describes was still in progress when the book was published, so I am left wanting more. I wish he had waited a few more years to write the book. Perhaps there will be a sequel.

I recommend this book for anyone interested in big cats and especially lions. I also recommend it as post-safari reading if you’re going to Africa. Since about one-third of the book is story after story of man-eating lions, I think it is best read in the comfort and safety of a building on a different continent (like New Zealand) instead of in a tent in African bush.

How this book has crossed my path numerous times:

First of all, in the summer of 2002 I worked at the Field Museum sorting tiny shells from microscopic ocean bottom sediment. The Man-Eaters of Tsavo have a prominent display on the main floor of the museum and I walked past them frequently. Shortly after ending my internship at the Field, I flew to Kenya to begin my semester-long program there with Earlham. Our group of 17 Earlhamites met at the Amsterdam airport and flew to Nairobi together. While I was in the Amsterdam airport, Bruce Patterson (the author) struck up conversation with me because we had been on the same flight from Chicago to Amsterdam and were continuing on the same flight to Nairobi. He was going to Kenya to lead a Field Museum expedition. We had a brief conversation about the Field Museum and such since I’d just worked there (though our paths never crossed in the Museum as far as I’m aware).

The Kenya program traveled to many places around the country, including the Taita Discovery Center located on the Taita-Rukinga Ranch situated between Tsavo East and Tsavo West National Parks. Taita Ranch was the location of Patterson’s lion radio collaring work to study the maneless lions of Tsavo. Teams of Earthwatch (www.earthwatch.org) volunteers had been out earlier in 2002 collecting data on ‘Romeo,’ the radio collared male. Well, one night while our group was at the Taita Discovery Center, we had the opportunity to go out in search of Romeo. They said there was no guarantee we’d find him- we might just drive around in the dark for hours with no lion sightings. About half of our group (regrettably including me) decided to stay at camp while the other half of the group quickly found Romeo and got to watch him mating with lionesses. The group who went came back around midnight positively wired with excitement. I decided to go to bed early and thus missed my chance to see the Romeo featured in Patterson’s book.

While I was in Kenya, I knew about the man-eaters of Tsavo. I knew that sometimes people were killed by wildlife (although elephants, hippos, and buffalo are the most dangerous). But I didn’t know that man-eating lions actually make a habit of it. I didn’t know that lions in search of the sweet taste of human flesh have gone into houses and tents and chosen one unlucky person from the lot to eat. Ignorance is bliss, and I was thankfully blissfully ignorant of these facts because I had an experience that was absolutely terrifying without this additional knowledge. A few of you have heard this story, but I think most of you haven’t and I think it is worth repeating because it is one of the most unforgettable experiences of my life.

In the middle of the Kenya program, we spent three weeks at a field station at Lake Naivasha, Kenya. During this time, we were doing small group projects for our ecology class. Many of us chose to work in the nearby Hell’s Gate National Park (I spent 30 hours observing zebras- you really can tell them apart by their stripes). Hell’s Gate is to small to support many carnivores or large herbivores such as elephants and rhinos, so it is one of the only game parks in Africa where you can walk around on foot. Shortly before our group arrived, a pride of lions was seen in the park, which was quite unusual. We saw a few lion tracks, but no lions. In Hell’s Gate they told us you just need to be sure if you’re walking through scrub with low visibility that you make lots of noise so you don’t startle any cape buffalo. Cape buffalo are vicious when startled and can maul a lion to death. If they know you’re coming, you’re ok, but for heaven’s sake don’t sneak up on them.

Near the end of our 3 weeks at Lake Naivasha/Hell’s Gate, I decided to go camping in the park with a few other students. One attempted camping trip in this park (by my friends Cody and Megan) was cut short when they were attacked by a menacing troop of baboons who broke into their cooler and ate all their food even before they’d set up camp. Still, I wanted to spend a night in the bush. My camping buddies were Alison, Teresa, and Justin. Our program leaders dropped us off at the campsite up on a hill about 3 km from the park gate overlooking the Hell’s Gate gorge. It was a beautiful place. We made a fire, cooked dinner, and stayed up until about midnight talking in the tent before we fell asleep. Our leaders would be back to pick us up at noon the next day.

I have no idea how long I was asleep before I awoke to the sound of something very large moving around outside our tent. Alison and Teresa were already awake. They shushed me when I tried to ask them what was going on outside. We lay there, hardly breathing, listening to the animals outside the tent. I couldn’t tell what the animals were, but I tell they were big. These weren’t baboons. It sounded like they were over at our firepit where we left a chicken carcass from dinner. Hyenas, I thought, they would eat the chicken bones. Then they would sniff their way to the rest of the food in the cooler, knock it over, and eat everything else. I waited for the sound of the cooler crashing, but it never came. I was too terrified to move. I was afraid that the sound of extracting my arm from my sleeping bag to check the time on my watch would attract them to my presence. Lions, I thought, Oh God that pride of lions is here. They’re going to sniff around the tent, smell our tracks going in and out, then rip through and eat me first because I’m lying next to the door. Hyenas might do that too. Or a leopard. I was petrified. Even if any of us lived through an attack, no one would be back to check on us until noon, and we’d sure die of blood loss before then. Opening a window flap to peek at our unwelcome visitors would have created far too much noise and possibly confirmed our presence inside the flimsy nylon shelter to suspicious predators. It was completely out of the question. I could see the headlines already: U.S. students killed in Kenyan game park and Earlham mourns the loss of four students. I have never in my entire life been so sure of the end. I really, truly, thought I was going to die.

This may seem overdramatic to you, but imagine for a moment how you might react if you were sleeping in a tent in Kenya far from safety and the only thing you knew about the animals outside was that they were big.

We heard the animals run past the tent. Then, about a meter from my feet, I heard riiiiiip munch munch munch. Riiiiiiiiip munch munch munch munch. That was the sound of an animal eating grass. Whew. It was an herbivore. At least it didn’t want to eat us. Alison, Teresa and I quietly came to consensus on the animals’ identity in the hushest of whispers: Cape buffalo, easily one of Africa’s most dangerous animals. If we startled them with a sudden noise, they could charge the tent and maul us to death in short order. An Earlham professor miraculously averted death in a buffalo attack years before in this same park. Justin was blissfully asleep for the whole affair, until Teresa woke him up for making too much noise moving in his sleep. I never looked at my watch, so I have no idea how long the ordeal lasted. Long after the last animal noise was heard, we went back to sleep. The next morning we saw the cape buffalo tracks all over our campsite.

As long as we were quiet and still, we had little to worry about with the buffalo. Apparently the campsite offers excellent midnight grazing. In retrospect, I'm able to laugh about the experience and the craziness of it, but nonetheless it was a reminder of my mortality. Our fear of being eaten by carnivores was probably exaggerated. Still, before we knew they were buffalo, I think I would have been even more convinced of my death (if that’s possible) had I read The Lions of Tsavo. If the pride of lions in Hell’s Gate were out to eat us, we wouldn’t have heard them coming since cats are expert stalkers. And I still think they probably would’ve eaten me since I was closest to the door.

After the program ended, I stayed in Kenya for a few extra days with Megan, Cody, and Alison. We all took the overnight train from Nairobi to Mombasa. It was during the construction of that rail line that tens of people were killed by the man-eating lions of Tsavo that are now stuffed for display at the Field Museum.

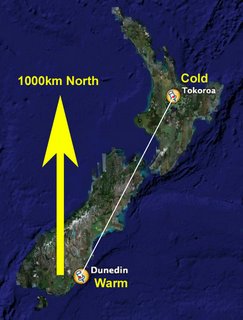

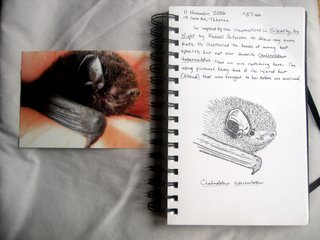

Now, four years (almost exactly) after my imagined death by lion, I came across this book at the Tokoroa Library. Just before I checked out this book, I decided to email Bruce Patterson. In addition to lions, he has done some work with bats. There are very few people working with bats in Africa, so I decided to email him about the possibility of working with him in grad school. I received a very positive response, so I might be applying to University of Illinois Chicago where he has a faculty appointment. Maybe I’ll get to see Romeo after all.

Carrie